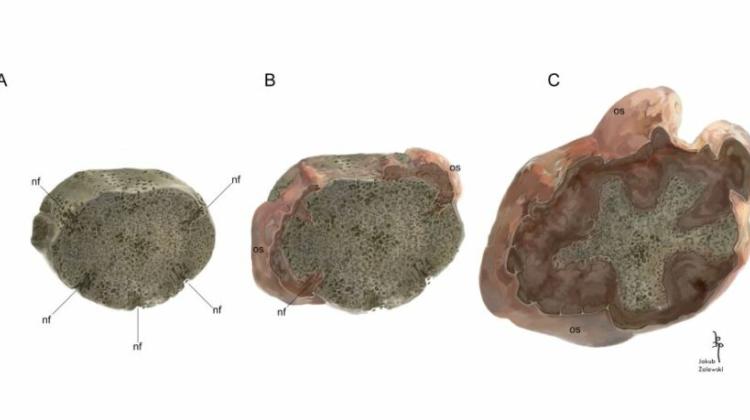

Prehistoric animals also suffered from cancer, say scientists

The reconstruction of growth of neoplastic tissue on the vertebral intercentrum ZPAL Ab III/2467 during ontogeny. A: the normal, ontogenetically juvenile intercentrum, with only a thin layer of the periosteal bone on the ventral part of the bone and visible nutrition foramina, nf reaching deep into the endochondral bone; B: the overgrowth of the neoplasm producing osteoid, os, the normal periosteal and neoplasm are deposited at the same time; C: during the growth the faster growing neoplasm gradually limit

The reconstruction of growth of neoplastic tissue on the vertebral intercentrum ZPAL Ab III/2467 during ontogeny. A: the normal, ontogenetically juvenile intercentrum, with only a thin layer of the periosteal bone on the ventral part of the bone and visible nutrition foramina, nf reaching deep into the endochondral bone; B: the overgrowth of the neoplasm producing osteoid, os, the normal periosteal and neoplasm are deposited at the same time; C: during the growth the faster growing neoplasm gradually limit

Malignant tumours, sometimes considered to be diseases related to environmental pollution, also affected prehistoric animals. A team led by a palaeontologist from the University of Silesia described the results of research on vertebral cancer of a Triassic amphibian discovered in Krasiejów near Opole.

The scientific paper by the team led by Dr. Dawid Surmik from the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the University of Silesia 'An insight into cancer palaeobiology: does the Mesozoic neoplasm support tissue organization field theory of tumorigenesis?' was published in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution.

In the description on the website of the University of Silesia, Surmik explains that traces of diseases occasionally found on the bones of prehistoric animals provide insight into their health problems. At the same time, they provide evidence of the ancient lineage of some diseases, some of which are hundreds of millions of years old.

Since palaeontological evidence is limited to fossilized bones, diseases that can be identified in fossil material must either affect the skeletal system directly, or indirectly affect the bones. These include some malignant tumours, commonly regarded as diseases related to the development of civilization and progressive environmental pollution.

“These factors undoubtedly increase the incidence of malignant tumours in modern times. However, cancer itself has a much longer history than civilization and even humanity as a whole. Studies of cancers in non-human animals, including those in evolutionarily old groups, such as coelenterates, show that the process of tumour formation is an evolutionarily primal phenomenon that has existed since the beginning of animal life on Earth,” Surmik said.

Neoplasm formation underlies the evolution and development of clonal multicellularity. Multicellular animals are characterized by a natural drive to constantly divide and differentiate body cells. The course of clonal divisions (those in which daughter cells form from one ancestral cell) is controlled and regulated by genetic mechanisms.

When this control is lost due to a mutation, uncoordinated cell division occurs, resulting in excessive growth of tissue mass. This is how, according to the widely accepted theory of somatic mutations, tumours form. Learning about and understanding the evolutionary history of neoplasms may indirectly contribute to the development of new therapeutic methods.

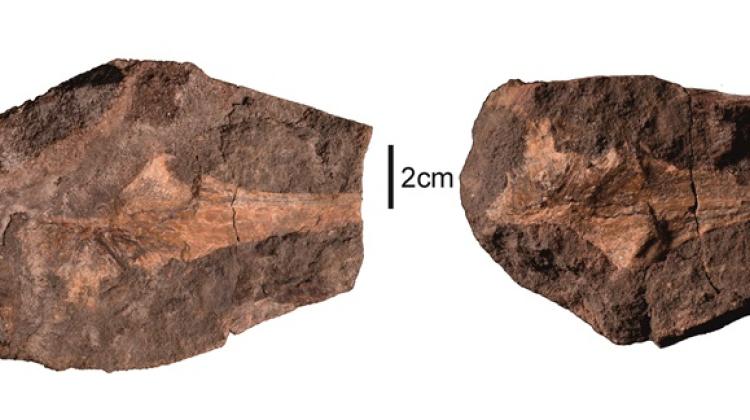

Fossil evidence of cancer in the form of growths or tumours has already been identified, for example, in dinosaurs and other prehistoric vertebrates. The interdisciplinary, international research team led by Surmik presented the results of the study of the vertebra of a Triassic amphibian Metoposaurus krasiejowensis, discovered in Krasiejów near Opole. On one of the vertebrae of the amphibian, belonging to the collection of the Institute of Palaeobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, scientists identified a growth that covered a large part of it. Researchers, in cooperation with the Faculty Laboratory of Computer Microtomography of the University of Silesia, used X-rays to investigate about the internal structure of this fossil.

The scans revealed that the pathological tissue grows on the outside of the vertebra and also inside it, penetrating deep into the bone through the natural nutrient channels in the vertebra. This showed that the cause of the growth was a malignant tumour. Further analysis of the scans showed that much of the vertebra's structure had been destroyed by the growth of pathological tissue.

The researchers cut the specimen and, by grinding its surface to a thin, semi-transparent, obtained a sample that could be observed in a microscope; modern tumour samples are analysed in a similarly way. The preparations provided information on the histological structure of the pathological tissue, especially the contact between the diseased part and the part not yet affected by the tumour.

On this basis, the researchers concluded that the cancer was osteosarcoma. Detailed studies yielded information about the dynamics of tumour growth, which was reconstructed in detail in their paper in BMC Ecology and Evolution.

According to the team, the malignant tumour identified in the metoposaur is one of the oldest examples of cancer in the fossil record and the only confirmed case of neoplasm in a fossil amphibian, as well as the best documented evidence of tumours in prehistoric animals, supported by evidence of microstructural studies.

The members of the team led by Dr. Surmik were: Piotr Duda from the Faculty of Exact and Technical Sciences of the University of Silesia, Justyna Słowiak-Morkowina, Tomasz Szczygielski and Dawid Dróżdż from the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Maciej Kamaszewski from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Elżbieta Teschner from the University of Opole as well as Dorota Konietzko-Meier and Sudipta Kalita from the University of Bonn (Germany) and Professor Bruce M. Rothschild of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Pennsylvania, USA).

The research was financed by the National Science Centre as part of the research project 'Osteopathology in the fossil record as a carrier of palaeoecological and palaeoepidemiological information'.

PAP - Science in Poland, Mateusz Babak

mtb/ pad/ kap/

tr. RL

Przed dodaniem komentarza prosimy o zapoznanie z Regulaminem forum serwisu Nauka w Polsce.